The Stop-Work-Order imposed by the Trump administration in January 2025 is a wakeup call to many developing countries including Somalia. Since the early sixties, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has been a significant contributor to Somalia’s development and humanitarian assistance, focusing on various sectors to promote stability and improve living conditions. Prior to the civil unrest in 1990, USAID played a crucial role in strengthening Somalia’s agricultural sector, infrastructure and human resource development. The agency was particularly supportive in the areas of agriculture research, education and development programs, which helped lay the foundation for modern agricultural practices and institutional capacity building.

The Stop-Work-Order imposed by the Trump administration in January 2025 is a wakeup call to many developing countries including Somalia. Since the early sixties, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has been a significant contributor to Somalia’s development and humanitarian assistance, focusing on various sectors to promote stability and improve living conditions. Prior to the civil unrest in 1990, USAID played a crucial role in strengthening Somalia’s agricultural sector, infrastructure and human resource development. The agency was particularly supportive in the areas of agriculture research, education and development programs, which helped lay the foundation for modern agricultural practices and institutional capacity building.

For nearly three decades USAID supported both irrigated and dryland agriculture research centers based in Afgoi and Baidoa, respectively. Improved farming practices, soil and water conservation strategies, irrigation infrastructure and superior varieties of cereals and legume crops were all developed, enabling local farmers to increase productivity despite challenging climatic conditions. In addition, numerous government employees benefitted from Master’s degree training at US Universities. Beyond agriculture, USAID contributed to Somalia’s education and health sectors.

IDP Maslah Camp| Photo by Farah Abdi Warsameh

USAID support resumed again a few years after the civil unrest in 1990 with a primary focus on humanitarian assistance targeting food security, emergency health services, water and sanitation, and support to displaced populations. These interventions provided life-saving assistance to millions of Somalis affected by famine, drought, and conflict.

In recent years, USAID has expanded its efforts beyond humanitarian aid to support long-term development and resilience-building initiatives. Key areas include: a) Governance; b) Economic Growth; c) Education; and d) Health.

|

USAID’s Financial Support to Somalia in 2023: A Breakdown of Assistance and Economic Growth Initiatives

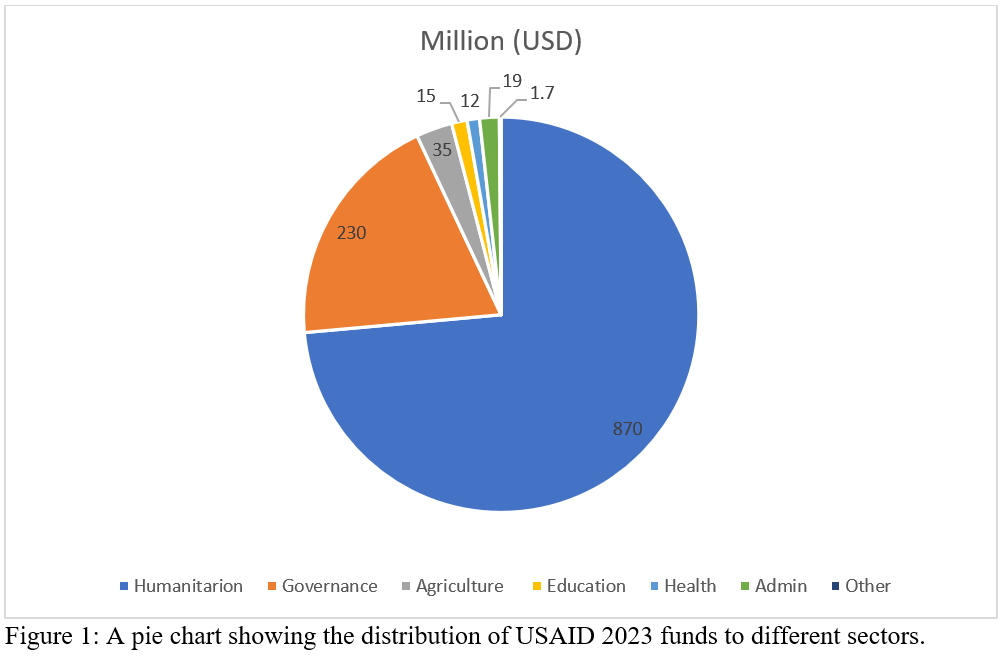

For the fiscal year of 2023 (Table 1), Somalia received approximately $1.18 billion in USAID-managed foreign assistance, accounting for about 2.4% of USAID’s total disbursements for the year 2023. Humanitarian assistance is by far the largest sector accounting for 73% of the total support while the health and population is the least supported. The shift toward economic growth support began in 2011 with the Partnership for Economic Growth (PEG) project, followed by the Growth, Enterprise, Employment, and Livelihoods (GEEL) and the Inclusive Resilience in Somalia (IRiS) initiative. The budgets allocated for these projects were $20.9 million, $74 million, and $65 million, respectively. Each project spanned a five-year period. |

|

Table 1: USAID support to Somalia in 2023 |

||

|

Sector |

Amount (Millions USD) |

Percentage (%) |

|

Humanitarian Assistance |

870 |

73 |

|

Governance |

230 |

19 |

|

Economic growth (crop, Livestock and Fisheries) |

35 |

3 |

|

Education |

15 |

1.3 |

|

Health and Population |

12 |

1.0 |

|

Administrative Cost |

19 |

1.6 |

|

Other |

1.7 |

0.1 |

|

Total |

1,187.7 |

100 |

Humanitarian Assistance

As indicated in Table 1 and Figure 1, humanitarian assistance is the largest area of support and is primarily implemented through partnerships with various non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and international agencies. These implementing partners play a critical role in designing and executing programs that address the urgent needs of vulnerable populations, particularly the substantial number of IDPs who have been affected by conflict, climate-related shocks, and economic instability.

As indicated in Table 1 and Figure 1, humanitarian assistance is the largest area of support and is primarily implemented through partnerships with various non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and international agencies. These implementing partners play a critical role in designing and executing programs that address the urgent needs of vulnerable populations, particularly the substantial number of IDPs who have been affected by conflict, climate-related shocks, and economic instability.

Among the various interventions, mobile cash transfers to IDPs remains the most common and widely implemented strategy. Through cash-based assistance, beneficiaries receive direct financial support, often via mobile money transfers, allowing them to purchase essential goods and services according to their specific needs. This approach not only enhances household resilience but also stimulates local markets by empowering displaced populations to make their own purchasing decisions. The cash assistance programs are particularly crucial in the face of recurring droughts, floods, and ongoing conflicts, which have left millions without reliable access to food and basic services. By prioritizing cash transfers, humanitarian organizations provide immediate relief while promoting transparency and flexibility for the recipients.

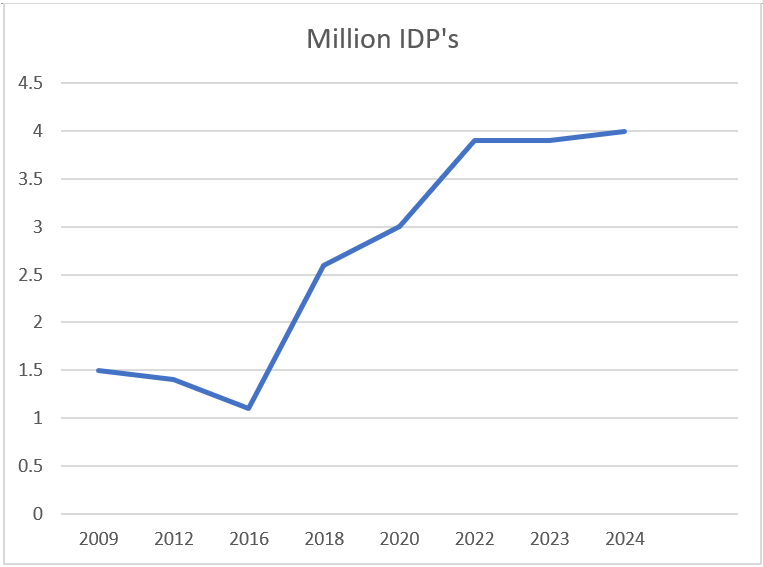

Internal Displacement in Somalia: Regional Distribution and Key Trends in 2023

As of the end of 2023, International Organization for Migration (IOM) reported approximately 3.45 million people living in internal displacement due to conflict, recurrent droughts and flooding. This figure aligns fairly well with the figures reported by IDMC and UNHCR. The regional distribution of the IDP’s is shown in Table 2. These figures highlight that the Banadir region, encompassing the capital city Mogadishu, hosts the largest proportion of IDPs, accounting for 31% of the total displaced population. The Bay and Gedo regions follow, hosting 17% and 10% of IDPs respectively. Overall, the southern and central regions of Somalia bear the highest concentrations of internal displacement (Table 2).

As of the end of 2023, International Organization for Migration (IOM) reported approximately 3.45 million people living in internal displacement due to conflict, recurrent droughts and flooding. This figure aligns fairly well with the figures reported by IDMC and UNHCR. The regional distribution of the IDP’s is shown in Table 2. These figures highlight that the Banadir region, encompassing the capital city Mogadishu, hosts the largest proportion of IDPs, accounting for 31% of the total displaced population. The Bay and Gedo regions follow, hosting 17% and 10% of IDPs respectively. Overall, the southern and central regions of Somalia bear the highest concentrations of internal displacement (Table 2).

Table 2: IDP distribution by region

|

Region |

Number of IDPs |

Percentage of Total IDPs |

|

Banadir |

1,070,944 |

31% |

|

Bay |

586,000 |

17% |

|

Gedo |

345,143 |

10% |

|

Lower Shabelle |

276,115 |

8% |

|

Galgaduud |

241,600 |

7% |

|

Hiraan |

172,572 |

5% |

|

Middle Shabelle |

138,057 |

4% |

|

Mudug |

103,543 |

3% |

|

Lower Juba |

103,543 |

3% |

|

Other Regions |

413,917 |

12% |

|

Total |

3,451,434 |

100% |

Challenges and Sustainability of Humanitarian Interventions in Somalia

Unlike other humanitarian interventions such as health and education, the food and cash distribution programs for IDPs in Somalia face significant challenges due to systemic corruption, diversion, and mismanagement. A major issue is the role of so-called “gatekeepers,” who control access to IDP camps and take a substantial portion of the allocated aid. It is widely acknowledged that nearly 50% of the cash intended for IDPs is misappropriated by these intermediaries, who then distribute portions of it among local authorities, landowners, and even the NGOs implementing the projects.

Power dynamics play a critical role in Somalia’s IDP camps, as the majority of displaced individuals come from minority and marginalized communities, while gatekeepers, landowners, and host communities typically belong to dominant clans. This imbalance places marginalized groups in an extremely weak negotiating position, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation and discrimination. Any attempt to challenge the authority of gatekeepers often results in harassment, restricted access to aid, or forced eviction, further deepening their insecurity and dependence on a system that does not prioritize their well-being.

Historically, when droughts affected certain regions, particularly dryland agricultural areas, displaced individuals and whole communities would migrate temporarily to irrigated farming zones in search of labor opportunities, returning to their original settlements once the rainy season resumed. In severe cases—such as the 1972/74 drought in northern Somalia—the government took the lead in relocating affected populations to irrigated agricultural areas, facilitating their reintegration into productive livelihoods. I’m delighted to have been part of the resettlement program where people affected by drought in Dar-Yare village near Las Anod were resettled to Kurtun-Waarey, a fertile agriculture land in the Lower Shabelle region.

Historically, when droughts affected certain regions, particularly dryland agricultural areas, displaced individuals and whole communities would migrate temporarily to irrigated farming zones in search of labor opportunities, returning to their original settlements once the rainy season resumed. In severe cases—such as the 1972/74 drought in northern Somalia—the government took the lead in relocating affected populations to irrigated agricultural areas, facilitating their reintegration into productive livelihoods. I’m delighted to have been part of the resettlement program where people affected by drought in Dar-Yare village near Las Anod were resettled to Kurtun-Waarey, a fertile agriculture land in the Lower Shabelle region.

Unlike previous interventions, the current formation of IDP settlements has become a long-term, unsustainable phenomenon, fostering dependency on food and cash aid. Displaced people are perpetually reliant on handouts in camps, with little prospect of integrating into host urban communities or transitioning to alternative livelihoods. Instead of providing temporary relief, these interventions have created a cycle of dependency, turning IDP settlements into permanent enclaves reliant on external assistance.

Moreover, food aid distribution has turned into a lucrative business in Somalia, raising concerns among many Somalis about whether these interventions are doing more harm than good.

The critical question remains: What alternative strategies can be implemented to create more sustainable and self-reliant systems? Unfortunately, neither NGOs nor government authorities have provided concrete solutions thus far, as both have become direct beneficiaries of the current ineffective system.

To address these challenges, it is imperative to shift from a short-term aid model to a more sustainable approach that focuses on livelihood support, skills development, and reintegration of displaced populations into the productive economy. Without meaningful reform, the current aid system risks perpetuating cycles of dependency rather than fostering long-term resilience.

A Sustainable Path Forward: Moving Beyond Aid Dependency

The prolonged reliance on food aid and cash distribution for Somalia’s IDPs has created a cycle of dependency that benefits gatekeepers and intermediaries while failing to provide long-term solutions for displaced individuals and communities. A key lesson from the Stop-Work Approach imposed by the Trump administration is the importance of re-examining unsustainable aid practices and reassessing intervention strategies. Instead of perpetuating reliance on external donors, NGOs, and development agencies, a shift is needed towards locally driven initiatives and sustainable solutions that empower IDPs to regain their dignity and economic independence.

Given that agriculture is the backbone of Somalia’s economy and many internally displaced persons (IDPs) come from farming backgrounds, scaling up agricultural interventions must be at the core of long-term solutions. Strategic investments in agriculture not only create sustainable livelihood opportunities for displaced communities but also enhance national food security, reduce reliance on imports, and stimulate economic growth. Resettled IDPs can significantly contribute to both irrigated and rainfed farming systems, playing a vital role in crop and livestock production.

To facilitate this transition, comprehensive interventions should focus on securing access to arable land, developing irrigation infrastructure, providing high-quality seeds and farming tools, and delivering training in modern agricultural techniques. Additionally, addressing systemic challenges—such as security risks and access to farming regions—is crucial. In this context, it is imperative to confront the broader issue of insecurity, whose influence continues to disrupt agricultural activities and rural livelihoods. Any meaningful effort to rehabilitate IDPs through agriculture must incorporate robust strategies to mitigate these threats and ensure a stable environment for long-term resettlement and economic recovery.

To facilitate this transition, comprehensive interventions should focus on securing access to arable land, developing irrigation infrastructure, providing high-quality seeds and farming tools, and delivering training in modern agricultural techniques. Additionally, addressing systemic challenges—such as security risks and access to farming regions—is crucial. In this context, it is imperative to confront the broader issue of insecurity, whose influence continues to disrupt agricultural activities and rural livelihoods. Any meaningful effort to rehabilitate IDPs through agriculture must incorporate robust strategies to mitigate these threats and ensure a stable environment for long-term resettlement and economic recovery.

Beyond subsistence farming, the private sector must be engaged as a key player in the long-term solution. Encouraging private investors to support agribusiness initiatives, such as commercial farming, food processing, and value chain development—will generate employment and market opportunities for resettled IDPs. Public-private partnerships can facilitate land access, provide financing for smallholder farmers, and integrate displaced communities into commercial agriculture. Additionally, microfinance institutions and cooperatives should be strengthened to offer financial services tailored to resettled IDP farmers and agriculture entrepreneurs.

Policy reforms are also essential to ensure a smooth transition from aid dependency to self-sufficiency. The government should work with the private sector to establish a framework that prioritizes the resettlement of IDPs in productive agricultural areas, enforces land tenure rights, and promotes climate-resilient farming practices. Furthermore, vocational training in agribusiness, irrigation management, and value chain development should be integrated into long-term development programs to equip resettled IDPs with the necessary skills for sustainable livelihoods.

Ultimately, shifting from short-term humanitarian aid to long-term economic empowerment requires coordinated efforts between the donors, government, private sector, and local communities. By transforming IDPs from aid recipients into productive contributors to the agricultural economy, Somalia can turn its displacement crisis into an opportunity for rural development, economic growth, and food security. The time to act is now—failing to transition from dependency to sustainability will only prolong vulnerability and instability for generations to come.

Dr. Hussein Haji

About the Author:

Dr. Hussein Haji, Ph.D., is the co-founder and former Executive Director of the Somali Agriculture Technical Group (SATG). With extensive research experience in Somalia and Canada, he has been a driving force in restoring Somalia’s agriculture. He also founded Filsan Inc., pioneering modern agribusiness solutions. His work bridges scientific research with practical applications to enhance food security and sustainability in Somalia.