Exploring Agricultural Resilience Enhancement in Somalia

This report was written to explore ways in which agricultural resilience in Somalia could be enhanced through improving farmer access to quality seed of superior varieties. Evidence from Somalia and elsewhere suggests that there are benefits to be gained from increased adoption of superior varieties if they are both adapted to the agro-ecological conditions found in the crop growing areas of the country and meet farmer and market needs.

Challenges Stemming from the Absence of Agricultural Research

Adaptation to the agro-ecological conditions can be inferred from varietal performance in similar agro-ecologies, but determining whether varieties meet farmer and market needs necessitates engagement with the farming and business communities. The superiority of a variety needs to be determined in-situ both by farmers and other end-users including traders and processors which requires that they be involved in variety evaluation. The absence of a functional agricultural research and extension system in Somalia for over three decades has resulted in the loss of institutional memory about socioeconomics, gender roles in agriculture, and the varied agroecological environments in which they operate.

Balancing Emergency Seed Interventions and Sustainable Systems

Increased weather variability, population displacements, erosion of farmer knowledge, changing market opportunities, and the prolonged non-functioning of an agricultural research and extension system are additional complicating factors that have resulted in significant changes to agriculture since the early 1990s. Emergency seed interventions have been used both in Somalia and elsewhere to improve seed security, but emergency seed interventions often disrupt longer-term efforts to develop sustainable seed systems.

Integrating Formal and Informal Seed Systems

The report draws upon a broad range of experiences from Somalia and elsewhere that highlight the resilience of informal seed systems and describes alternative ways of addressing seed insecurity than provision of physical seed. These include supporting the development of the formal seed sector in ways that are appropriate to a fragile state such as Somalia and building on the strength of informal seed systems. The report also illustrates that it is possible to link elements of both formal and informal seed systems in an integrated manner to scale up the production of quality seed of superior varieties of non-hybrid crops.

This integrated approach is increasingly being referred to as the intermediate seed system and often focuses on the production of QDS and/or Standard Seed by farmers. These systems are most appropriate for self-pollinated crops like cowpea and mung bean where loss of varietal integrity is minimal, somewhat less so for open-pollinated crops like sorghum and sesame but inappropriate for hybrids. Such crops’ ability to maintain varietal integrity makes them less attractive for commercial seed production (because farmers can recycle seed over several years), and they require less stringent quality control systems than those necessary for hybrid seed production. The report proposes a dualistic approach for seed sector development in which seed of self and open-pollinated crops are produced by farmers, whereas hybrid crops (for which a regular supply of fresh seed is needed) are produced, marketed, and distributed by commercial seed companies.

MONITORING AND TRACEABILITY IN SEED PRODUCTION

The introduction of superior varieties through all three seed systems – formal, intermediate, and informal – requires access to quality early generation seed from which subsequent generations are multiplied. Although small quantities of breeder and basic seed can be obtained from International Agricultural Research Centers (IARCs) that exist to produce International Public Goods (IPGs), mechanisms need to be developed to scale-up the production of EGS that are initially required for on-farm testing but also further seed production. EGS production requires following seed production protocols that can be monitored and certified by competent authorities. EGS production is not commercially attractive which means that public-private partnerships are needed to scale up EGS production and to ensure broad access to EGS.

NURTURING SEED POLICIES AND REGULATORY FRAMEWORKS

Seed policies, laws and regulations are needed to guide the development of the formal seed sector without undermining the resilience and benefits delivered through informal and intermediate systems. These should be co-created with interested parties, including legal expertise, in the form of a legal guide that details the roles and responsibilities of all parties and at the same time be sufficiently flexible to accommodate crisis modifiers and resource constraints.

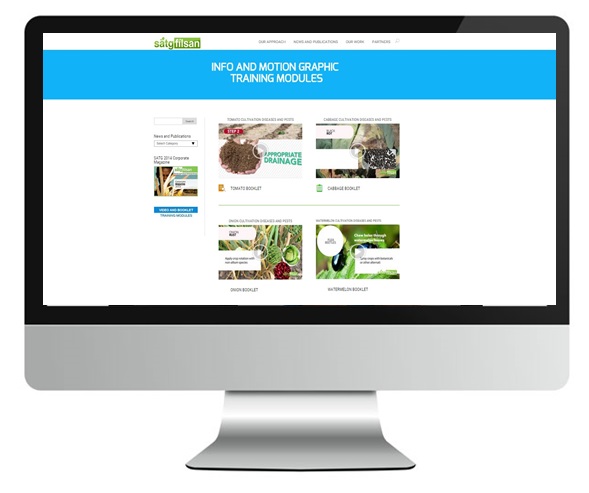

Regulatory authorities need to expand their role from policing to seed system development. Seed is only differentiated from grain through the application of well-developed seed production protocols. It is imperative that systems are put in place to monitor seed production and ensure traceability without which the development of formal and intermediate seed systems will be compromised. The training and licensing of self-employed seed inspectors, the use of commercially available apps for traceability and monitoring and point of sale verification systems that farmers can use through mobile phone technology are commercially available and easily transferred to Somalia with its well-developed mobile phone and money transfer infrastructure.

The use of commercially available apps for traceability and monitoring and point of sale verification systems that farmers can use through mobile phone technology are commercially available and easily transferred to Somalia with its well-developed mobile phone and money transfer infrastructure.

Innovative Approaches to Engaging Farming Communities

Engagement with farming communities and other end-users both in Somalia and elsewhere was traditionally done through publicly funded extension services. In Somalia the collapse of formal extension is increasingly filled by a mix of non-governmental organizations and humanitarian agencies, but interventions are often short term and lack continuity needed to initiate and follow through on variety testing and subsequent scaling up following a project life cycle approach. The emergence of agrodealers provides a distribution network for commercial seed companies while the recruitment of Village Based Advisors, VBAs who provide small seed packs for on-farm testing and complementary advice can support both seed marketing and distribution leading to accelerated varietal adoption. Extension messages can be reinforced through a mix of radio, television, and social media but messaging must be well-informed and delivered in imaginative ways.

Empowering Female Traders in Somalia's Seed System

Female traders in Somalia’s informal seed system are thought to be key in supplying good quality farmer-produced seed to areas where seed is needed, e.g., in places that have been affected by localized drought. This provides a potential entry point to engage them to play a role in the sale of quality seed of superior varieties for a range of crops that could include linking them to individual farmer entrepreneurs provided with a source of quality EGS as well as to commercial seed companies.

Leveraging Somalia's Youth and Entrepreneurial Spirit

Somalia has a young population, a vibrant business community and strong entrepreneurial culture all of which can be harnessed to support the introduction and scaling up of superior varieties and complementary inputs that are needed to increase resilience and productivity. However, there is an urgent need for government, humanitarian agencies, and development actors to work together in a more coordinated way to support the development of an intermediate seed system that both builds on the strengths of the informal system while at the same time fostering the growth of commercial seed companies. Experience from other countries has shown that the introduction and farmer adoption of superior varieties will follow different trajectories dependent on the breeding system of the crop but also local capacity and market demand. These factors are dynamic, and policies, laws and regulations must be framed to accommodate and support changes that are relevant both to the fragile state and to the needs of all its farmers.

Article written by ~ Dr. Richard B Jones | Board Chair, SATG

Recent Comments